Of course you know what a computer mouse is. Everyone does. In fact, you’ve probably got one in your hand right now. But if I told you what it was originally created for, you’d be shocked.

When Doug Engelbart patented the computer mouse on this day in 1963, he intended it to be a tool to transform the human race. And it was a revolution left unfinished.

The simple mouse was meant to be a simple tool as part of a grand plan to use computers to augment human intellect and increase our “collective IQ” – a visionary idea that was neglected and unfunded.

A Dream of Building Better Humans

There was a time when the computer science community thought the name Doug Engelbart was synonymous with “a crackpot”. He was a man with big, wild ideas – but he had not always been that way.

At the start of his life, Engelbart had simple plans of getting a “steady job, getting married, and living happily ever after.” He had spent some time as a radar technician during WWII, and was studying a PhD in Engineering at UC Barkley.

Shortly after getting married, Engelbart realized his career ambitions were nearly non-existent. And over several months, he came up with a guiding philosophy that would change the course of history.

- Engelbart decided that he would focus on trying to make the world a better place. The world’s problems were getting more complex, and so we needed to rise to meet the challenge.

- Any serious effort to meet this challenge and make the world better couldn’t be done alone. It would need some organized effort – one that harnessed the collective human intellect of all people to create an effective solution.

- He believed if you could dramatically improve the efficiency that people work on problems (Their ‘Collective IQ’), you’d be boosting every effort on the planet to solve important problems.

- He believed that computers could be the vehicle for improving people’s people’s Collective IQ, not just for crunching data.

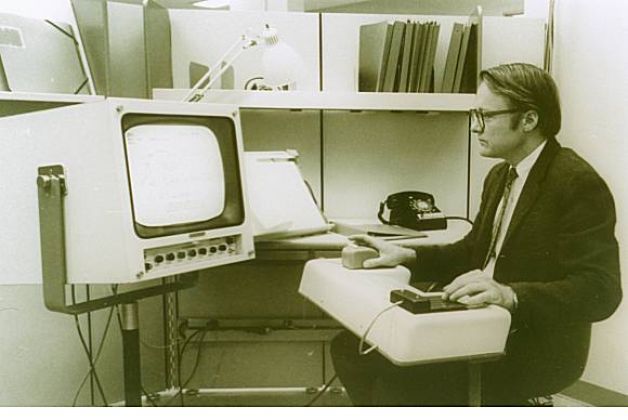

As a radar technician, he’d seen how information could be displayed on a screen. Decades before the personal computer, he began envisioning people sitting in front of cathode-ray-tube displays, “flying around” in an information space where they could formulate and portray thoughts. This would allow them to better harness their otherwise untapped sensory, perceptual and cognitive capabilities. It would also let them communicate and collectively organize their ideas with incredible speed and flexibility.

In short, back in 1951, Engelbart was sitting around and imagining using PCs to browse the internet and use Microsoft Teams. And in the computer science industry, this quickly made the name “Doug Engelbart” synonymous with “a crackpot”.

In fact, once he completed his PhD and became an acting assistant professor, he was tipped off by a colleague that if he kept talking about his “wild ideas”, he’d stay stuck in his role forever. In fact, through his entire life, he warned by people in both academia and the computer industry that using computers for anything other than computations and business data was “crazy” and “science fiction.”

Not one to go with the flow, Engelbart joined up with Stanford Research Institute (Now SRI International), and earned a dozen patents working on things like magnetic computer components and miniaturization scaling potential. He had also worked for the precursor to NASA (NACA).

Of Mice and Men

For most of his life, had two struggles: getting people to take his ideas seriously, and getting out from the shadow of his most well known accomplishment – the computer mouse.

Only for one decade did he get significant backing. In 1963, the U.S. Defense Department gave him the funding and ability to assemble a team. With it, he assembled a team of computer engineers and programmers at his Augmentation Research Center (ARC).

His idea was to free people’s minds about computing being about calculations, and make it about augmenting the capabilities of the human mind (‘Augmented Intelligence’). Over six years with funding from NASA and ARPA, he put together the elements that would make such a machine a reality.

And in 1968, he performed what is considered in retrospect to perhaps be the most important computer demonstration of all time – an event now called “The Mother of all Demos“.

The team demonstrated the results of their work: the NLS System, which stood for “oN-Line System”. It was the first system to employ the use of hypertext links, raster-scan video monitors, information organized by relevance, screen windowing, context-sensitive help, integrated hypermedia e-mail, and of course, the computer mouse. And the whole demo was done by shared-screen teleconference over modem – another historic first.

As Engelbart moved his mouse across the screen – highlighting text and resizing windows – people stopped thinking of him as a crackpot. By the end, he was described as “dealing lightning by both hands.”

When he finished, the audience gave him a standing ovation. The future of modern computing had been demonstrated for the first time. The demo had even introduced the concept of collaborative document creation (aka Wikis). History had been made.

The Ideological Divide

It’s worth noting that Engelbart had spoken during the Mother of All Demos about how the computer was designed for Augmented Intellect and increasing humanity’s IQ. A theory of technological coevolution.

But this was not what people had taken away from it. And arguably, it would be Engelbart’s and his ARC program’s downfall.

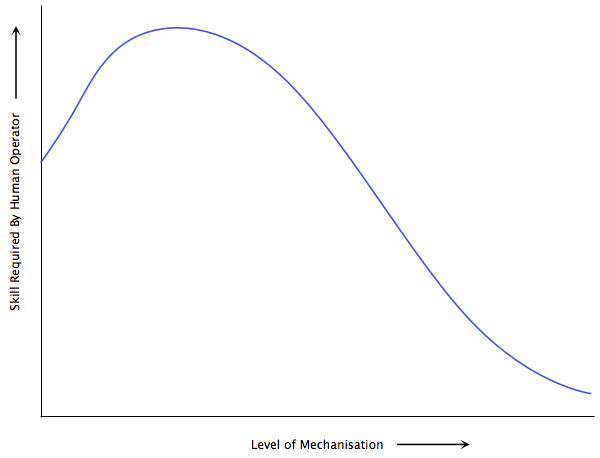

The NLS had been designed with a difficult learning curve. This was by intentional design – it was made for an educated user, and rewarded learning. In fact, Engelbart was dismissive of ease-of-use. And ease-of-use is everything in the mass market.

“Engelbart, for better or for worse, was trying to make a violin… most people don’t want to learn the violin,” Alan Kay said of Engelbart’s failed vision.

In fact, it was an ideological divide that split Engelbart from his team. Many of his researchers left his organization for Xerox PARC. Where Engelbart saw a future with collaborative, networked computers (and time-sharing still had a place), younger programmers felt personal computers were the future. The argument was historically situated: the younger programmers came from an era where centralized power was suspect, and personal computing was just on the horizon.

In many ways, history both sides with and against Engelbart’s crusade. The automation and deskilling of human operators – and the rise of Artificial Intelligence – means that low-skilled users are the trend. From an economic point of view, it costs less and takes less time to have unskilled employees.

On the other hand, these days people are hardly as skeptical of centralized power as the 1960’s. Collaborative, networked computers are the norm, and one could argue that servers are an far more evolved form of time-sharing.

The Mouse Becomes an Elephant

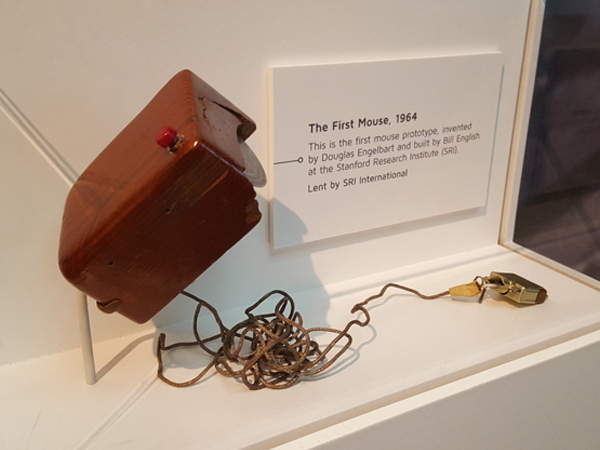

The computer mouse was meant to be a small footnote to Engelbart’s goals. But instead, it became everything anyone wanted to talk about.

“Along the way we needed to have a gadget that would be a better windshield wiper or something, but the whole rest of the expedition had so many other things, it just wasn’t a big deal,” Engelbart said.

He said while the original mouse was designed with a tail-like cord coming out the back – hence the name ‘mouse’.

Unfortunately, Engelbart didn’t get rich off his invention. In an interview, he said “SRI patented the mouse, but they really had no idea of its value. Some years later it was learned that they had licensed it to Apple Computer for something like $40,000.”

After the exodus of his staff, he slipped into relative obscurity and was marginalized for a time. Engelbart expressed disappointment in interviews in the 1980’s and 2000‘s that while computing power had increased by millions of times, his vision of human augmentation had not.

Towards the end of his life, he set up the Doug Engelbart institute to promote his vision. In December 2000, Bill Clinton awarded him the National Medal of Technology, the U.S.’s highest technology award. In fact, his mouse prototype is encased in the Smithsonian.

Moore and Engelbart

Now if you’re in IT, you’ve probably heard of Moore’s Law (which may be under threat). What you may not know is that Moore – the co-founder of Intel – was inspired to write this law after sitting in on a speech made by Engelbart. He had been talking about how at the time aerospace engineers made tiny models and then scaled them up – and how computing technology would involve taking chips and scaling them down.

Engelbart’s papers and speeches on chip miniaturization directly affected Moore, who wrote a paper on his famous law a decade later.

If you’re feeling bad that Engelbart doesn’t have his own law, don’t. He actually does, though it’s nowhere near as famous. Unsurprisingly, it’s called Engelbart’s law.